How to generate motivation is one of the biggest challenges of modern humanity. Adults openly struggle with it. And it’s a daily challenge for teachers and parents to figure out for our children.

For months, we’ve been exploring topics related to motivation, including engagement, flow, focus, and self-regulation (inclusive of mindfulness).

Engagement has been the most recent fascination. What does the word engagement mean? To educators? To marketers? And game designers? What does it mean to aim for engagement in education? What does algorithmic engagement do to us? Especially when it is embedded in everything?

It’s still an active exploration. But one clear critique of engagement is starting to emerge. The way engagement is defined by educators leads you to overlook an important biological narrative about motivation. This is what we’re going to explore now.

That said, we’ve also been finding that getting past engagement doesn’t bring perfect clarity about motivation either. Focus, flow and self-regulation are all important topics with rich scientific support. But they all offer incomplete views on motivation with big questions unanswered.

Earlier this year, a mountain of an idea came together. What if looking at focus, flow and self-regulation together gives us a more complete view of the experiences that generate and sustain motivation?

Motivation is the desire to work towards goals. Biologically speaking, dopamine and testosterone play the largest role in motivated behavior. The former motivates reward or goal seeking, the latter makes effort enjoyable (yes, testosterone is necessary for men and women).

Flow—or optimal experience—is conceptually most closely associated with goal orientation and enjoyment. We think of the experience of flow as one the greatest contributors to human progress. It leverages dopamine, testosterone, and a cocktail of other neurochemicals and hormones to fuel it. It is considered enjoyable and desirable. So it is with some justification that many think flow is the experience to aim for when trying to generate and sustain motivation.

Most educators use the word engagement instead of flow and have adapted its definition to incorporate it. The problem with this adaptation, is that not all engagement is flow (ie, many consider excitement engagement—but this is very different biologically and often works against building focus and motivation). And this can lead educators to think flow is far more commonly occurring than it really is.

And importantly here, we think it is becoming apparent that true flow doesn’t necessarily lead to sustained motivation after experiencing it either (ie, gamification produces flow, but in the extreme leads to the perception “reality is broken” — a decidedly unmotivated statement about everyday life).

Flow and focus are closely related concepts. Flow is often described as intense focus. And this makes sense, given that what kicks flow into gear is tension not calm. This is a common misunderstanding of flow, actually. And it is why self-regulation on its own doesn’t create flow or motivation. It can only aid finding focus and calm.

But here again, there are some important differences between flow and focus that make separating the concepts helpful.

Most enjoyable activities are not natural; they demand an effort that initially one is reluctant to make.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Where focus, or control of attention, differs is that it is a struggle. It is a productive struggle, but a struggle nonetheless. It isn’t enjoyable. You bounce back and forth between boredom and anxiety. It provokes stress. This struggle comes with all sorts of biological responses, for example, neurochemicals like cortisol and epinephrine that prime you for action.

Why is focus such a struggle? The likely reason is that our biology evolved to make us distractible. This helped us avoid getting attacked and eaten by surprise—which was a good thing. But this fact doesn’t make the negative experience of focus any more appealing.

Until the last quarter century, we overcame this negativity and found our focus. This was likely because we had less options for what to do with our attention and didn’t have pervasive cultural narratives telling us stress is bad (which is true, but only if stress is sustained—short durations of stress are healthy and necessary).

To summarize—our biology works against us finding focus. If we struggle productively for a spell, then our biology kicks in and works with us to sustain it and find enjoyment. We call this experience the Motivation Mountain.

The reason why we call it Motivation Mountain, is because as an experience progresses, the resulting flow leaves you in balance. That means normal levels of rest can restore the biological fuels (ie, dopamine and testosterone) needed to repeat the cycle over and over again. This is the essence of creating sustained motivation from a biological perspective.

As is probably self-evident, we tend to have an aversion to stress and suffering. So it is no surprise that there are aspects of this mountain that are immediately unappealing, however biologically true. In addition, we now have the pervasive societal narratives bombarding us saying that stress is bad everyday, which further discourage the necessary struggle.

We have a hunch this is one of the reasons why the concept of focus has also been rolled up into engagement. We’re trying to bury this inconvenient truth.

The tactics of engagement, whether inside or outside education, tend to explicitly aim to minimize or shortcut the struggle of focus for this reason. We use novelty to gain attention. We use variable rewards to almost trick minds into sustained focus. We turn these methods into algorithms to further optimize them. This benefits us when we need to get someone’s attention. But we also end up using more of the biological fuels for motivation in the process.

That said, it works. People play video games endlessly. They scroll social media infinitely. Gamified classrooms gain better engagement. People attest that these experiences create flow with a high degree of regularity.

The problems only become apparent when you consider the impacts on motivation. Let’s explore why back on Motivation Mountain.

When you shortcut the struggle of focus, the resulting flow more likely drops you into a biological state of depression. We’ll refer to this as the Engagement Canyon. Neuroscience has proven that reward (i.e., reaching a goal) that isn’t preceded by effort and struggle both diminishes your dopamine levels and testosterone levels. This means the stress of normal, non-gamified focus is actually required to avoid this biological drop. You need that shot of cortisol and epinephrine to build up your dopamine and testosterone levels to be able to experience flow that sustains.

And if you skip this step, you have to rest longer or engage in more self-regulation like meditation or intense physical training to regain biological balance. More rest and more self-regulation than most of us do. Likely, our normal “balanced” state is already way down in the canyon and we don’t even know what balanced feels like anymore, and research is proving this in diverse ways.

Starting the next experience that requires focus already in the canyon makes focus much, much harder. It provokes a greater sense of boredom, more anxiety, and ultimately more stress. The effort feels too great to even consider at times. You end up being driven by your impulses (ie, you are easily outraged, or can only pay attention to something with pre-existing interest) and not what you choose to pay attention to. You avoid the necessary anxiety and stress. And the only way you can focus again is with even more engagement tactics (or superhuman resilience).

Engagement Canyon is a recipe for losing sustained motivation, and virtually extinguishes the possibility of flow from non-gamified life.

Understanding how Motivation Mountain works gives us hope. Flow preceded by productive struggle is the kind of flow that sustains motivation. This means to generate and sustain motivation you just need to experience finding focus regularly and have a stronger rest/self-regulation routine to support it.

This is where self-regulation comes back into the motivation picture. To get to flow, you need to increase the tension of your focus, not seek calm. You need to sustain the struggle longer. Mindfulness is proven to help you sustain focus. Certain mindsets and self-regulation activities can help you better handle that boredom, anxiety and stress that comes with increasing the intensity of focus until your biology kicks in and takes you into flow. And if you are starting out at the bottom of Engagement Canyon, you need more of this. Much more to reach the kind of focus where flow can be found again in everyday life.

With effective self-regulation to aid focus, each new experience can progress towards flow that sustains motivation.

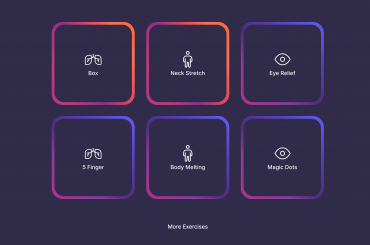

This is why we are calling it the skill of focus. Focus is now inclusive of self-regulation, in recognition of the fact that we’re all starting out in canyons. Meditation, breathing and visual exercises and mindfulness can be used as tools to help you increase the tension until you find the sustaining kind of flow you need for enjoyment and productivity. We focus on this skill more than the other elements of Motivation Mountain, because this is the part that everyone is trying to skip over.

As life morphs closer to a video game, this gets to be of particular importance. TikTok, Fortnight, on-demand delivery and more are dropping us all into Engagement Canyons daily. Maybe even by the minute. It is not a leap to claim that focus has been diminished at scale, in every demographic and every age group. And it will continue to get worse as technology gets even better at optimizing for your engagement (i.e., the Metaverse).

A wide scale loss of ability to focus on everyday activities (i.e., just listening to each other in a conversation) is a solid explanation for many of our societal challenges. This is also a good explanation of why it has been characterized that kids “don’t want to learn anymore”. And further, why there continues to be greater and greater prevalence of attentional disorders.

If focus is the skill our present and future needs, educators and parents play an important role. They should be asking themselves some versions of these questions:

Are you going to help children climb Motivation Mountains by investing in the skill of focus?

Are you willing to help children confront the challenge of climbing out of Engagement Canyon?

Can you resist or limit throwing them back into Engagement Canyons in exchange for other goals (ie, convenience, learning standards, etc.)

Regardless of whether you are a parent or teacher, we all have to start deciding between mountains and canyons for ourselves.