Focus is the control of attention. We believe this is the correct definition.

But as we’ve learned over the last 6 months, control is a word with some complications and nuances. It provokes a reaction, whether consciously or not.

For it to be a useful word towards building the skill of focus in students and ourselves, it needs more clarity. So we will dwell on its meaning here today.

Early in our journey, we met some of the wonderful members of the Self-Reg community. Without pause, and with more than a few graphics included of their models, they immediately challenged our use of the word control.

Central to their method is the idea that traditional self-control is a failed behavioral model. There is substantial evidence that it fails to work and sets people up to live with disabling levels of stress. Or worse, it can bring out some darker sides of us if the ideal is embodied too tightly. The Self-Reg model is designed to combat this – to make self-regulation the better alternative. As they say, “Self-regulation makes self-control possible, not the other way around.”

And we believe they are right.

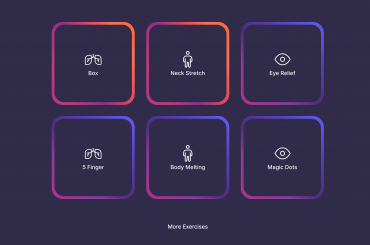

At first we were a little surprised by the strength of their response. We were admittedly less concerned with the problems of self-control at that time. And we were already onboard the self-regulation bandwagon as the ideal driver of control of attention. Self-regulation activities and routines to help manage the stress of focus were already central to the Focusable experience we were building. So we listened to their arguments and tuned both our understanding and the experience we were building based on their insights.

Despite this, we feel that there is something important about the word control worth holding onto.

You see, focus is stressful. It’s called productive struggle for a reason. And even though the stress is good stress – eustress – it is often hard to tell in the moment. This is true even for those of us with a highly developed sense of self-awareness. Stress has a way of making things foggy. So foggy that it is easy to view good stress as bad in the moment and simply give up.

And if we give up too often, we wither. Our attentional abilities are like muscles in that they are antifragile. They atrophy without good stress and get stronger with it. And with atrophy comes not only a lesser ability to focus, but also it would seem a greater sensitivity to other things. The reason why we feel so overtaxed is not just the stresses of modern living, but because our attentional capabilities have withered away from too many gamified technology experiences.

Temporarily embracing the objective of control helps bring clarity to this foggy situation. It avoids setting expectations for self-awareness under stress that most of us could simply never achieve.

The key in our minds is to place timed limits and couple it with a healthy self-regulation routine to rest and recover. In this way, our control of attention is strengthened like our muscles. Our capacites can grow and our overall sensitivities to stress and anxiety are reduced.

We believe the objective of control in this limited way is an important step towards meaningfully improving the quality of your life.

Yet we should note that as our journey has progressed, we also started to realize why the Self-Reg community is so forceful on this point. Simply put, there are many educators still stuck in the throes of the ideal of self-control.

You can tell you’ve met someone who thinks this way when they claim to have no difficulty focusing whatsoever. They set out to do what they want to do and get it done. And they often think they can just teach the skill of focus to their students with a few lessons. Just show them how to do what I do and they’ll be on the right path, they think. It is also frequently the same educators who think removing access to phones from classrooms is a good idea. They fail to see how this choice mirrors failed models for managing addiction and could actually strengthen unhealthy relationships with technology.

The irony is that this approach has the highest potential of building a disabling mindset about focus. If students don’t feel trusted to control their attention and are held up to impossible behavioral ideals, it can lead to apathy – perhaps even distress when they fail.

It also frankly shows little awareness of just how stacked the deck is against kids gaining control of their attention. Like the fable of John Henry, no single educator can keep up with the machines on their own. There are just too many distracting experiences kids do and will experience over a lifetime.

This stacked deck is why we believe that technology must also play a role here. Solutions need to move at the speed of attention and stay with students well beyond the classroom – perhaps even over the course of a lifetime. Frankly, we all can regress on our attentional abilities. It’s not like those of us who grew up before the internet are perfect at managing our attention now.

To make the skill of focus a priority in education we need a whole new framework – one built around the idea of self-regulation and the limited embrace of control of attention, not self-control.

It would need to be built around an understanding of attention spans for each grade-level, as well as methods to assess each individual student’s capabilities. It would need to leverage tools that help students both in and beyond the classroom. And it would include scaffolded learning experiences that meet students within their proximal zone of focus development – progressing them from basic to more challenging focus experiences. Who knows, perhaps the traditional lecture might have a place in this framework – it is a learning experience with maximum “resistance” to focus after all.

All of this is to explain why we’re not only building a tool, but also investing in the development of these frameworks with the educators in our Optimalist community. We are also looking forward to working more closely with the Self-Reg community to help minimize unnecessary distress as we aim to maximize student’s capabilities to focus.

Onwards.